Hogyan értelmezhetőek az orthodox/ hászid zsánerképek?

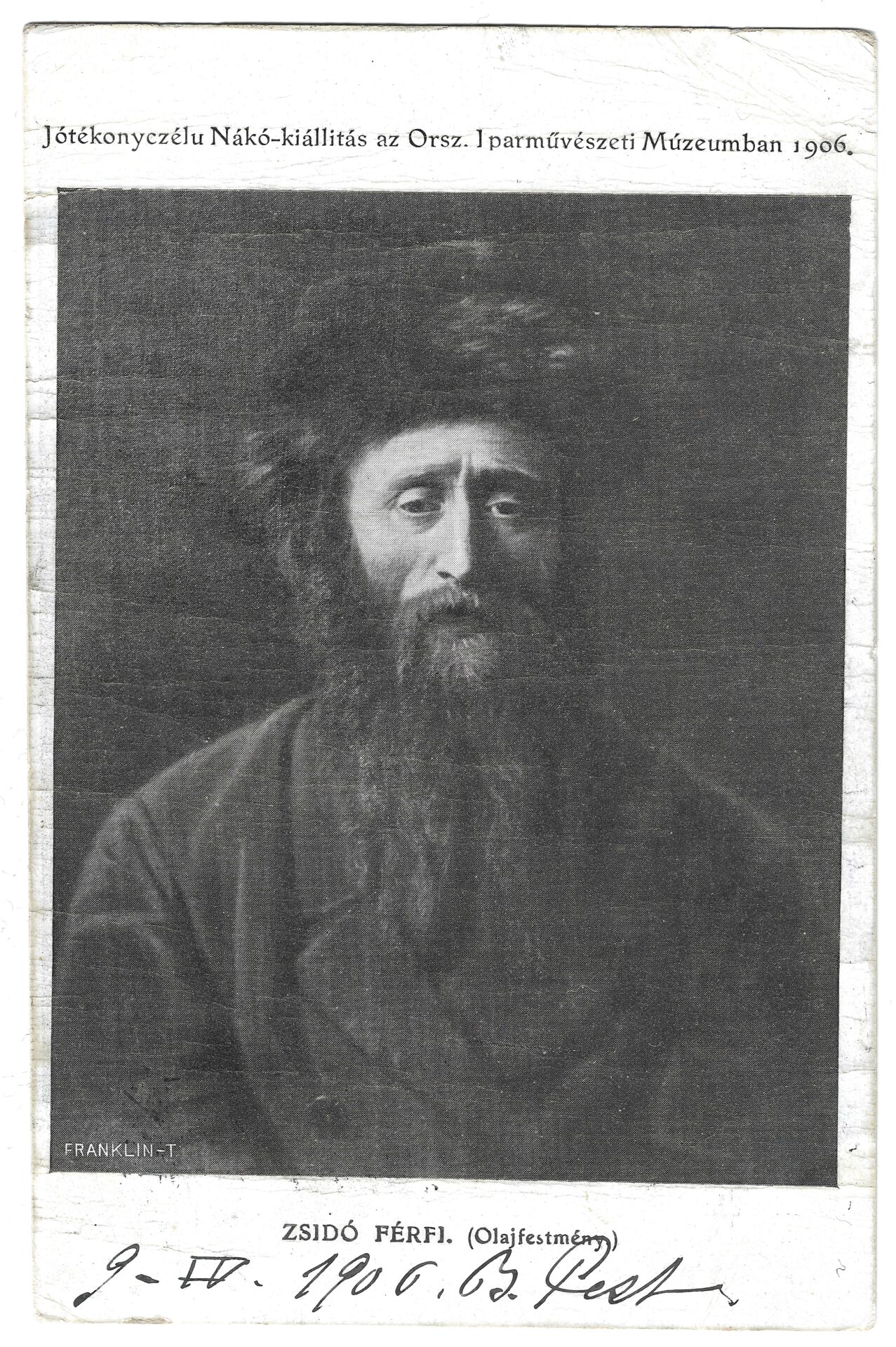

A képeslap a 19. század utolsó harmadában a polgári átalakulás során a kis- és középpolgári rétegek számára meggyorsította a világ megismerésének lehetőségét, ugyanakkor nem csak lehetővé tette, hanem fel is keltette e megismerés utáni igényt. A judaica tárgyú képeslapok az egzotikumot iránt fogékonyak számára készített zsánerképek és népéleti jeleneteket ábrázoltak. Alkalmi kiadójuk között jelent meg a munkácsi Kroó Hugó, a prágai Lederer & Popper, az oroszországi Mnachem Fr. P. Schofer, a csernovici Schiller fotográfiai műintézet, a két világháború közötti időszakból a munkácsi Gloria kiadó és az izraeli jisuvok beállított életképeit bemutató Jamal Bros. Fürdőhelyek és a különböző települések zsinagógáiról a helyi könyvkereskedők és fényképészek jelentettek meg képeslapokat. Az ünnepi üdvözlőlapok többségén csak a készítés helyére (Németországra) vagy a behozatal tényére („import”) utaltak. Ezek jó része sorozatban megjelent, szövegezetlen képek voltak, amelyet Magyarországon nyomtak felül. Az orthodox és hászid zsidókról csoportképeket a zsinagógákat megjelenítő képeslapok is tartalmazhattak. Az egzotikum és az etnográfiai szempont lehet a magyarázata, hogy Gróf Nákó Kálmánné festményeinek jótékonysági kiállítása 1906-ban Országos Magyar Iparművészeti Múzeumban közép-európai hagyományos rabbi portréját is bemutatta. A kelet-európai zsidónak a viselet és szokásleírásai más üzenettel jelentek meg 1915 előtt az Egyenlőség kulturmissziós írásaiban: a hászid alakja a beilleszkedésre való képtelenség jegyeinek hordozójává lett. A kulturmissziós diskurzus összefonódott a megreformált judaizmus univerzalista erkölcsi missziójával is, ami a judaizmus eszkatológikus vonásait értelmezte át. A zsidóság új történelmi küldetésében az ideális zsidó a modernitás élharcosa lett, aki példát mutat az emberiség egészének. Küldetésének lényege Mezei Ernő publicista és függetlenségi politikus megfogalmazásában, „hogy a maga kijelölt helyén, pusztán saját sorsának példájával előítéleteket tördössön, új igazságokat felmutasson és terjesszen, s a felvilágosodás hadsorainak kifogyhatatlan tartaléka, az emberiség haladásának becses kovásza maradjon.” (Egyenlőség 1913. szept. 28./ 4-5. Az örök zsidó [Írta:] Mezei Ernő)

How to interpret the Orthodox/Hasidic genre images?

In the last third of the 19th century, during the bourgeois transformation, the postcard accelerated the possibility for the middle and lower middle classes to get to know the world, while at the same time not only enabling but also awakening the need for this knowledge. Postcards on Judaica depicted folkloric scenes and genre scenes for those with a taste for the exotic. Among their occasional publishers were Hugó Kroó of Munkác, Lederer & Popper of Prague, Mnachem Fr. P. Schofer in Moscow, the Schiller Photographic Institute in Chernivtsi, the Gloria publishing house in Minsk, and the Jamal Bros. Local booksellers and photographers have published postcards of bathing places and synagogues in various towns. Most of the holiday greeting cards only referred to the place of production (Germany) or the fact of importation (“import"). Many of these were serialised, blank images overprinted in Hungary. Group pictures of Orthodox and Hasidic Jews may also have been included on postcards showing synagogues. The exoticism and ethnographic aspect may explain why a charity exhibition of paintings by Countess Kálmán Kálmán Nákó in 1906 at the National Hungarian Museum of Applied Arts included a portrait of a traditional Central European rabbi. The dress and customs of the Eastern European Jew had a different message in the cultural missionary writings of Egyenlőség before 1915: the figure of the Hassid became a bearer of the traits of inability to assimilate. The cultural missionary discourse was also intertwined with the universalistic moral mission of reformed Judaism, which reinterpreted the eschatological features of Judaism. In the new historical mission of Judaism, the ideal Jew became a champion of modernity, an example to all humanity. The essence of his mission, in the words of Ernő Mezei, a publicist and independence politician, is “to break down prejudices in his own appointed place, to proclaim and spread new truths, and to remain the inexhaustible reserve of the enlightenment’s armies, the precious leaven of human progress." (Egyenlőség 28 Sep 1913 / 4-5. The Eternal Jew [By:] Ernő Mezei)

Rabbi portréja. Képeslap az Iparművészeti Múzeumban 1906-ban rendezett jótékony célú kiállításról

Portrait of a Rabbi. Postcard from the 1906 charity fundraising exhibition at the Museum of Applied Arts

© Glässer Norbert