Miért nem kívánatosak az „opera tündérei” az orthodox otthonban?

A vidéki és városi orthodoxia hitbuzgalmi aktivistáinál mindvégig tapasztalható volt az összzsidóságon belüli univerzális valláserkölcsi felelősség és az intő szándék. Az orthodox problémafelvetések, amelyek a családok és az ifjúság vallásosságát a városi élet olyan tömegjelenségeitől törekedtek megóvni, mint az operaelőadások, a mozi és a vallással ütköző új ideológiák, – azon túl, hogy az orthodox zsidó hitbuzgalom jelenségei voltak – egy szélesebb társadalmi diskurzusba illeszkedtek. Ennek témái – a kor problémájaként – más felekezetek vallási megújulási törekvéseiben is feltűntek. A hitbuzgalommal a magyar nyelvű orthodox sajtóban – a szentéletű asszonyok mellett – annak a nőnek az alakja is megjelent, aki orthodox szempontból a modern (nagyvárosi) deviancia nyomait viselte magán. Amikor róla írtak, akkor a hagyományosnak tekintett női szerepeket helyezték vele szembe. Ezek a viták és a hozzájuk tartozó nőképek a családi és intézményi vallási szocializáció jelenségeire vonatkoztak. A világi sajtó és a szépirodalmi olvasmányok jelenléte az orthodox nők körében a két világháború közötti időszak zsidó hitbuzgalmának egyik kulcskérdésévé vált. „…több u. n. jó zsidó, közepes vallásossági életmódot folytató családnál az anya péntek este és a szombati nap folyamán, ideje javát egy ismert szinházi lap tanulmányozásával tölti. Amikor a vallásos férj péntek este a sabosz angyalait üdvözli: »sólajm aléchem máláché hasorész« köszöntéssel, addig neje szinházi tündérekről és egyéb démonokról szóló történetekben talál élvezetet. Mire fog ez vezetni? Milyen zsidó anyák nevelődnek ilyen anyák és ilyen szellem mellett?” (Zsidó Ujság 1929. jan. 26./ 2. Péntek este orthodox háznál – Kohn Sámuel (Büdszentmihály).) A hitbuzgalom – összzsidóságban gondolkodó – fenti fejtegetése a hagyományos zsidó nőkép egyik fontos sajátosságára mutat rá: a judaizmus csak a megélt és követett példa révén adható át. Igaz ez az anyaszerepre is, tekintettel arra, hogy a vallási szocializáció a lányok esetében nem ölt olyan intézményi keretet, mint a fiúkat befogadó Talmud-iskolák. A családi otthon és a család keretében megjelenő modern minták ezért a közösség fokozott figyelmét és ellenőrzését igényelték. A vallás megélése közösségen belül közügynek számított.

„sólajm aléchem máláché hasorész” = Békesség reátok, szolgálattevő angyalok… – a hagyomány szerint, ahogyan találják az angyalok a szombatot fogadó családot, akképp fognak eljönni a rákövetkező szombatok is.

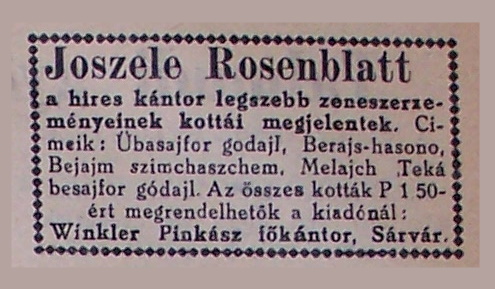

Az orthodox családokban az opera előadások helyett inkább opreaénekesi teljesítményt nyújtó orthodox kántorok liturgikus énekeit hallgatták. Ilyen volt az orthodox szempontból elfogadott Joszele Rosenblatt is.

Why were the “fairies of the opera” unwanted in Orthodox homes?

The zealous activists of rural and urban Orthodoxy have always had a sense of universal religious responsibility and intention of warning within the collective Jewish community. Orthodox suggestion of problems, which sought to protect the religiosity of families and the youth from mass phenomena of urban life such as opera performances, cinema and new ideologies that conflicted with religion, were not only phenomena of the Orthodox Jewish faith movement, but also part of a wider social discourse. Its themes were also present in the religious renewal efforts of other denominations, as problems of the times. With the religious fervour in the Hungarian language Orthodox press, the figure of the woman who bore the marks of modern (metropolitan) deviancy from an Orthodox point of view appeared alongside the idealized women of holy life. When they wrote about her, they contrasted her with the traditional roles of women. These debates and the associated images of women were concerned with the phenomena of family and institutional religious socialisation. The presence of secular press and literary fiction among Orthodox women became a key issue in the Jewish religious movement of the interwar period. “…in many so-called good Jewish families of moderate religious observance, the mother spends most of her time on Friday evening and Saturday studying a well-known theatre magazine. While the religious husband greets the angels of the Shabbos on Friday night with “sholem aleichem malach ha shores", his wife finds pleasure in stories of fairies and other demons of the theatre. Where will this lead? What kind of Jewish mothers are brought up with such mothers and with such a spirit?" (Zsidó Újság 26 Jan. 1929 / 2. Friday evening at an Orthodox house – Samuel Kohn (Büdszentmihály).) The above reflection of the zealous movement – thinking in terms of Jewishness as a whole – points to an important feature of the traditional Jewish image of women: Judaism can only be transmitted by example lived and followed. This is also true of motherhood, given that religious socialization for girls does not take place in the institutional framework of Talmudic schools as for boys. The modern patterns that emerged in the family home and family framework therefore required increased attention and scrutiny from the community. The practice of religion within the community was a public matter.

‘sholem aleichem malach ha shores’ = Peace upon you, oh ministering angels… – tradition says that as the angels find the family that receives the Sabbath, in that way will the Sabbaths that follow come as well.

In Orthodox families listened to liturgical hymns by Orthodox cantors who performed as opera singers rather than opera singers’ performances. Such was the case with the Orthodox-accepted Joszele Rosenblatt.

Zsidó Újság 1934. november 16./ 7. Joszele Rosenblatt kottáinak hirdetése.

Zsidó Újság, 16 November 1934., p. 7. Advertisement for sheet music by Yossele Rosenblatt.

© OR-ZSE Könyvtára

Csatolmányok

| Név | Méret |

|---|---|

| Yossele Rosenblatt - Shir Hamaalos Mit kell tudni? | 559 KB |